One aspect of Zerah Pulsipher’s life that has caused concern for his descendants over the years is his 1862 Church trial. The most famous account comes from his quorum president Joseph Young’s records on the Seventy:

Zera Pulsipher transcended the bounds of his priesthood in the ordinance of sealing, for which he was cited to appear before the First Presidency of the Church, and was dropped, by the instruction of President Brigham Young. He was subsequently ordained a Patriarch.”[1]

Assistant Church historian Andrew Jensen builds upon Young’s account and adds a few details:

He [Zerah Pulsipher] transcended the bounds of the Priesthood in the ordinance of sealing, for which he was cited to appear before the First Presidency of the Church, April 12, 1862. It was there voted, that he be rebaptized, reconfirmed and ordained to the office of a High Priest, or go into the ranks of the Seventies. Subsequently he was ordained a Patriarch. Elder John Van Cott was chosen as his successor in the First Council of Seventies…. He died as a member in full fellowship in the Church.[2]

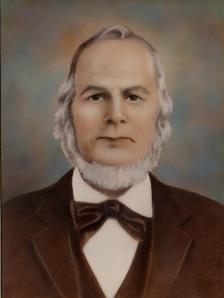

Image courtesy LDS Church History Library

Some confusion has existed in the past on the subject, since neither of the accounts above explicitly state that Zerah was disfellowshipped or excommunicated—just that he was tried before the First Presidency, rebaptized, and given the opportunity to become a high priest. When one individual expressed his or her confusion about the subject and asked for information on Zerah being excommunicated on a family history site, one response was that:

Zera Pulsipher was not ex-communucated [sic]. He was released from the Qurom [sic] because it was found out that he was a Seventy. He later on was set apart as a Pariarch [sic] in St George area. There were also a few others in those early days that were made Seventies and had to be released but not excummicated [sic].[3]

On the other hand, however, Lyndon W. Cook—an expert in early Mormon history—concluded that Zerah had been “either disfellowshipped or excommunicated.”[4] So, was Zerah excommunicated, disfellowshipped, or simply released from office?

We learn a few things about the details of the trial from letters and journal entries made around the time of the event. Sometime around February of 1862, it seems that Brigham Young had been alerted to a few unauthorized polygamous marriages performed by Zerah Pulsipher and had requested more information on the matter from Zerah’s Bishop, Frederick Kesler. The bishop gathered details of the incidents and reported his findings in a letter to President Young. The letter states, in essence, that Zerah performed two polygamous marriages for a Wm Bailey. The first took place in the summer of 1856, when Zerah married a widow by the name of Hannah Hughes to Bailey, though that marriage later ended in a divorce. The second took place in November of 1861 with a girl named Harriet Pareter (possibly Porter). In both of these cases, Kesler noted that “all this marrying has been done over Jordan under the jurisdiction of the 16th ward with out my approbation or concent in the least.”[5]

The second of the two marriages seems to have been more problematic in the eyes of Church officials. Kelser stated that, “Wm Bailey asked me for a recommend to you [Brigham Young] fer to get another wife. I told him to call again, which he did accompanied with the girl which he intended to marry (a Harriet Pareter) they were on their way to your office. I did not feel justified in giving him a recommend & referred him to you in person. He accordingly saw you & returned home took the girl called on Zera Pulsipher & he married them on the 28th day of Nov. 1861.”[6] According to Zerah’s son-in-law, John Alger, what happened between Bailey’s visit to President Young’s office and the wedding was that, “Old man baly came to father [Zerah] Puslipher some time a go and told him that President Young told him to go to him father Pulsipher and that the he should marry a cirtain girl to him Baly which father Pulsipher done,” which Alger called an “over sight” on Zerah’s part.[7]

With the information in hand, the First Presidency called together a hearing for Zerah Pulsipher to determine his standing in the Church. Wilford Woodruff noted in his journal on 12 April 1862 that: “I went to the Seventies Hall and attended the trial of Zera Pulsipher, who had been sealing women to men without authority. He was required to be rebaptized and had the privilege of being ordained into the High Priests Quorum.”[8] The next day, John Alger wrote a letter to some of his family in which he noted that “I was at the Council & so was Thomas we were well satisfiede with the council on that ocasion as they shoed [showed] every respect towards him possible under the cercumstances”, though the Bailey sealings “caused him to loos his standing in the Presidency.” Alger went on to state that, “We are all very sorry that he commited such an over sight But it is as it is and cant be helped it is a very hard loss in his old age.”[9]

Interestingly enough, Zerah’s autobiographies barely mentions the trial at all, covering up what it was when it is mentioned. In his last known autobiographical sketch, Zerah merely states that: “I had much labor to attend to attend among the seventies . . . I discovered that with age that I had approacht to that it began to wair upon my constitution I was advised by some to give up my presidency and let a younger man tak it that would be better qualified to attend to the labours that involved upon it I therefore gave it with the prilege of remaining in the body of the seventies or join the high priest chorum.”[10] Here we have a different view of the trial and the results—that Zerah was released, at least in part, due to his age and health. We know from the other, more contemporary records that that wasn’t the only reason he was released from his presidency, but it does seem to play into it, something we’ll consider later in greater detail.

In approaching the question of excommunication or disfellowshipment, there are a few different points to examine, including the nature of Zerah’s transgression and the nature of the ruling of the trial—specifically his ordination as a high priest and his rebaptism. The first of these to look at, perhaps, would be the nature of his transgression and how it was viewed at the time. Polygamy and the sealing ordinance have a long and complex history in the Mormon movement. It seems that Joseph Smith, Jr. had some idea of plural marriage in the early 1830s and developed the idea during the Nauvoo era, when he began to introduce the principle to other men. Apostle Amasa Lyman once said about the early attempts to practice plural marriage, “We obeyed the best we knew how, and, no doubt, made many crooked paths in our ignorance.”[11] Indeed, during Joseph Smith’s lifetime, the practice of plural marriage was performed in secret and sometimes even involved sealings to women who had previously been wed to other men. These conditions bred a situation of confusion and discord that, in large part, led to Joseph Smith’s death. Some men, such as John C. Bennett, took advantage of this confusion to seduce some Mormon women in Nauvoo, claiming that they were following Joseph Smith’s lead. Even after Joseph’s death and the subsequent migrations to Winter Quarters and Utah, a few instances of this sort continued to happen.

Perhaps in an attempt to prevent the confusion that occurred in Nauvoo, Joseph Smith outlined that, “there is never but one on the earth at a time on whom this power [the sealing power] and the keys of this priesthood are conferred” and that Joseph Smith was the one to hold the power in his time.[12] Even Hyrum Smith—Joseph’s brother, associate president, patriarch, and right-hand man did not have the right to use this power without permission, even though he had been given the authority “that whatsoever he shall bind on earth shall be bound in heaven; and whatsoever he shall loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.”[13] According to Brigham Young, when Hyrum officiated in some plural marriages without the Prophet’s approval, he was chastised by Joseph, who said that if Hyrum did it again without authorization, “he would go to hell and all those he sealed with him.”[14]

After the Quorum of the Twelve assumed leadership of the Church, they again asserted that “no man has the right to Attend to the ordinance of sealing except the President of the Church or those who are directed by him so to do.”[15] This belief would continue in the Mormon movement during the Utah period. For example, Albert P. Rockwood of the First Seven Presidents of the Seventy instructed a group of men in Provo, Utah, that, “[I]f you whant a wife, you first ask Brigham, then the Perants & next the female.”[16] During the Mormon stay in Winter Quarters, Brigham Young taught that this line of authority was used, in part, to reduce occurrences of Mormon men going

to some woman that does not understand which is right or wrong and tell her that she cannot be saved without a man and he has almighty power and can exalt and save her and likely tell her that there is no harm for them to sleep together before they are sealed, then go to some clod head of an elder and get him to say their ceremony, all done without the knowledge or counsel of the authority of this church.

“This,” Brigham stated, “is not right and will not be suffered.”[17]

With this in mind, it is not surprising to find that, as Young’s biographer John Turner wrote, “In numerous instances, Young disciplined followers for performing sealings without his blessing.”[18] For example, in 1847, Brigham Young complained that apostles Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor had committed adultery by marrying plural wives without his permission. He declared that they had “committed an insult on the Holy Priesthood.”[19] This so incensed Young that after Pratt had been murdered while serving a mission in Arkansas ten years later, he stated that when “Bro. Parley’s blood was spilt, I was glad for it for he paid the debt he owed, for he whored.”[20] Pratt and Taylor seem to have believed that since they held the sealing keys and acted as members of the Quorum of the Twelve (the Quorum, at the time, governed the Church without a First Presidency), they were allowed to perform sealings as they deemed necessary and right, even without express permission of President Young. Their view, however, had lost out to Brigham Young’s view of only the President being able to authorize plural marriages long before Zerah was tried for performing unauthorized sealings.

As for how such incidents were managed, there seems to have been inconsistencies in procedure. Both Parley P. Pratt and John Taylor were held as guilty of adultery because of unauthorized marriages on November 16, 1847, however, they got off with a sever chastisement while William W. Phelps was excommunicated on December 5, 1847 for the exact same offence.[21] The present author has had difficulty in discovering other sources that indicate how similar infractions of plural marriages performed without receiving President Young’s permission were handled, particularly during the era Zerah was put on trial.

It is significant that in the Kesler letter, Zerah’s bishop noted quite pointedly that, “all this marrying has been done over Jordan under the jurisdiction of the 16th ward with out my approbation or concent in the least,”[22] indicating that a break in procedure over lines of authority was a part of the problem. Interestingly, the Alger letter indicates that Bailey told Zerah that Brigham Young had authorized the marriages (even though Young apparently had not done so). This complicates the situation, since it indicates that Zerah was somewhat unwittingly conned into performing the sealings, but was still dropped from the presidency and rebaptized. It is also worth asking, if Zerah’s infractions were serious, why would he have been ordained a high priest right away? Unfortunately, the solution to understanding the incident in light of these considerations isn’t entirely clear. It seems that Zerah’s two main oversights were not approving the sealings with the bishop and not checking in with President Young to make sure that he had authorized the marriages. Perhaps in releasing Zerah, Church leaders were following standard procedure or felt they and to release him to avoid a scandal. It is also possible, given those oversights and Zerah’s age, the First Presidency simply felt that Zerah could no longer handle his duties in the presidency and released him, as Zerah indicated in his own records. Again, the reasons are not clear—we just know the reason the trial was convened and that as a result, Zerah was rebaptized, ordained a high priest, and dropped from the presidency of the seventy.

Looking closer at the Zerah’s suggestion that he was released because of his age, it is worthwhile to examine the nature of his calling and release. The family forum commenter referenced at the start of this essay stated that Zerah was released from the quorum because it was found that he was a seventy. In and of itself, the statement doesn’t quite made sense—it was probably understood that one of the First Seven Presidents of the Seventy would be a seventy—however; there is some validity to the idea behind the statement. During the 1830s, Joseph Smith, Jr. directed that Seventies “may preside over a church or churches, until a High Priest can be had. The Seventies are to be taken from the quorum of Elders, and are not to be High Priests.”[23] Some bickering had occurred before Joseph made the above statement as to whether high priests or seventies were greater in authority, and a council was held on 6 April 1837. Rather than determining which was the greatest, President Smith seems to have decided to just separate the high priests and seventies, inviting all seventies who had previously been ordained high priests to return to the high priests quorum and fill their place in the seventies with other men.[24] The records state that on this occasion:

It was ascertained that all but one or two of the presidents of the Seventies were High Priests, and when they had ordained and set apart any from the quorums of the Elders into the quorum of Seventies, they had conferred upon them the High Priesthood also. This was declared to be wrong, and not according to the order of heaven… and such of the Seventies as had been legally ordained High Priests were directed to unite with the High Priest’s quorum.[25]

Brigham Young indicated that this decision was meant “to satisfy the continual teasing of ignorant men who did not know what to do with authority when they got it,”[26] but it became solid policy until the 1960s—if a man was ordained a high priest, he could no longer be a seventy.

Several times throughout his ministry as a seventy, Zerah was pushed towards being released either so he could be made a high priest or so that a younger, more serviceable man could be called to his place. On 28 November 1845, the Quorum of the Twelve decided to release him and have him enter the high priest’s quorum, but for some reason, the action was not carried out.[27] During the infamous Mormon Reformation of 1856, both Jedediah M. Grant and Heber C. Kimball of the First Presidency threatened to drop Zerah Pulsipher along with several others of the First Seven Presidents of the Seventies for perceived underperformance in their duties.[28] The day after President Kimball’s remarks, Wilford Woodruff, along with “Brother Snow and Brother Richards… all advised the First Presidents of the Seventies to go forward and present a resignation of the Presidency to President Young and let some man take that place who could magnify it. Hancock and Z. Pulsipher said they would.”[29] This sort of thing wasn’t uncommon during the Reformation (several members of the Quorum of the Twelve did the same),[30] and Zerah later recorded that:

I with the associates of my Council went before Brother Brigham and informed him that if he knew of any others that would take our places better, magnify it for the interest of the Kingdom than we could, he was perfectly at liberty to do so, but he told us to go and magnify our calling ourselves.[31]

As referenced above, for the time being, Zerah “had much labor… among the Seventies remaining councilor,” but noted that,

I discovered that with age that I had approached that it began to wear upon my constitution, I was advised by some to give up my presiding and let a younger man take it that envoked upon it. I therefore gave it with the privilege of remaining in the body of the Seventies of join the High Priests Quorum.[32]

While the infraction of rules and subsequent trial were probably embarrassing to Zerah, and it would be understandable that he would leave those details out, his statement may be accurate in that it indicates the trial’s outcome had as much to do with being an opportunity to release Elder Pulsipher from his duties in the seventies quorum as any transgressions he had committed.

In connection with the issue of Zerah’s priesthood, we must also consider Andrew Jensen’s statement that Zerah was reconfirmed. In considering the question of Church discipline, the present author is not aware of reconfirmation being associated with anything other than excommunication, even in the early days of the Church. It is very possible, however, that the Jensen account may be inaccurate—it is the only account that mentions reconfirmation, and it is the last of the main sources available to have been written—being written 30 or 40 years after the event. While Jensen was meticulous in his work in the Church history department, he was not perfect and may have misunderstood Pulsipher’s ordination to the high priesthood as a reconfirmation of priesthood and membership. If it is true that Zerah was reconfirmed, however, it would be a strong indication of a temporary excommunication. Even if such a thing did take place, it did not seem to have been a major deal, asides from being released from the presidency of the seventy. After the trial, Zerah was still honored and given the chance to serve in a variety of priesthood offices and callings over the remaining ten years of his life, including that of a high priest, a presiding elder in the town of Hebron (roughly equivalent to a branch president today), and as a patriarch, dying as a member in full fellowship and honor in the Church.

A final point that must be discussed when it comes to understanding the results of the trial is why Zerah was required to be rebaptized. Today in Mormonism, rebaptism is an ordinance associated with excommunication—a member is entirely cut off from the Church and must go through the entrance ordinance again to be restored to membership. This was not always the case, however—during the 19th century, Mormons often viewed rebaptism as an ordinance for repentance, recommitment, and health. For example, the members of the 1847 pioneer brigade that began settling the Great Salt Lake City were all rebaptized in City Creek, with the explanation that, “[W]e had as it were entered a new world and wished to renew our covenants & commence in newness of life.”[33] During the Mormon Reformation, repentant Saints were encouraged to renew their covenants by rebaptism. In fact, when President Jedediah M. Grant died during the middle of the Reformation (probably from pneumonia), it was suggested that his death was at least partly due to his willingness to baptize so many penitent sinners in winter waters.[34] Again, when President Young began to institute the United Order of Enoch in Utah, he and hundreds of his followers were rebaptized to show their commitment to this order, with the words, “I baptize you for the remission of sins [and the] renewal of your covenants with a promise on your part to observe the rules of the United Order.”[35] So, while Zerah was rebaptized after the trial, it was not necessarily a sign that he had lost his membership. It could have simply been a sign of repentance for his transgression and recommitment for the future.

In summary, in 1862, Zerah Pulsipher was put on trial for performing unauthorized polygamous marriages for a man by the name of William Bailey. As a result of the trial, Zerah was dropped from his position as a general authority, required to be rebaptized, and given the privilege of being ordained a high priest. The nature of his offense seems to have been based on an oversight in the proper procedure for approving polygamous marriages. His release from the presidency, however, may have been more due to his age and ability to perform his calling than his to transgression, though whether Zerah was actually excommunicated or disfellowshipped remains unclear. In light of the forgoing evidence, though, I suggest that he was not stripped of his membership, even temporarily.

Post updated 16 December 2014

[1] Joseph Young Sr., Pamphlets, History of the Organization of the Seventies, [Salt Lake City: Deseret News Steam Printing Establishment, 1878], 6.

[2] Jensen, Andrew. L.D.S. Biographical Encyclopedia. Vol. 1. [Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1901], 194. [Online] http://contentdm.lib.byu.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/BYUIBooks/id/3527, accessed 13 Nov 2012

[3] https://familysearch.org/learn/forums/en/showthread.php?t=5952, accessed 13 Nov 2012.

[4] Lyndon W. Cook, The Revelations of the Prophet Joseph Smith: A Historical and Biographical Commentary of the Doctrine and Covenants (Provo, Utah: Seventy’s Mission Bookstore, 1981).

[5] Frederick Kesler letter to Brigham Young, February 7, 1862, Brigham Young office files, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[6] Frederick Kesler letter to Brigham Young, February 7, 1862, Brigham Young office files, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[7] John Alger letter, 13 April 1862, in Zerah Pulsipher Papers, circa 1848-1874, MS 753 fd 2, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[8] Wilford Woodruff, Wilford Woodruff Journal, 12 April 1862.

[9] Alger, Letter, 13 April 1862.

[10] Zerah Pulsipher, Autobiographical sketch #3, p. 29, in Zera Pulsipher record book, circa 1858-1878 MS 753 1, Church History Library (Church Archives), Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah

[11] Amasa Lyman, discourse of 5 April 1866, JD 11:207.

[12] D&C 132:7

[13] D&C 124:93-94

[14] Brigham Young to William Smith, August 10, 1845, Brigham Young Collection, LDS Church Archives. Cited in Irene M. Bates & E. Gary Smith, Lost Legacy: The Mormon Office of Presiding Patriarch [Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press: 1996], 67.

[15] Wilford Woodruff Journal, 24 July 1846. Cited in Waiting for the World’s End, ed. Susan Staker [Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1993], 93.

[16] Cited in Turner, Brigham Young, 240.

[17] John D. Lee Journal, 16 February 1847 in Journals of John D. Lee, ed. Charles Kelley (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1984), 80

[18] Turner, Brigham Young, 159.

[19] Cited in Gary James Bergera, Conflict in the Quorum: Orson Pratt, Brigham Young, Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2002), 58.

[20] Cited in Turner, Brigham Young, 271.

[21] D. Michael Quinn, The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1994), 660.

[22] Frederick Kesler letter to Brigham Young, February 7, 1862, Brigham Young office files, LDS Church History Library, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[23] D.H.C. 2:477.

[24] James N. Baumgarten, “The Role and Function of the Seventies in L.D.S. Church History,” Master’s Thesis (Provo, Utah: Brigham Young University, 1960), 21-22.

[25] D.H.C., 2:476.

[26] Brigham Young in Deseret News, 26 (June 6, 1877): 274.

[27] D. Michael Quinn, The Mormon Hierarchy: Origins of Power (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1994), 574.

[28] President Grant stated that, “they are asleep and ought to be dropped. I think that Brother Joseph [Young] ought to Cut them off & prune the trees around him…. When I vote for Rockwood, Pulsipher, Harriman & Levi Hancock I do it very reluctantly, & I have done so for years.” (Wilford Woodruff Journal, 7 October 1856.) President Kimball stated that, “here are brother Pulsipher, Herriman and Clapp, members of the first Presidency of the Seventies, sitting here as dead as door nails, and suffering these poor curses to live in our midst as Seventies. As the Lord God Almighty lives, if you do not rise up and trim your quorums, we will trim you off, and not one year shall pass away before you are trimmed off.” (JD 4:139-140.)

[29] Wilford Woodruff Journal, December 22, 1856.

[30] See, for example, Teachings of the Presidents of the Church: Lorenzo Snow (Salt Lake City: Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2012), chapter 8.

[31] Zerah Pulsipher, “History of Zerah Pulsipher,” in Thomas S. Terry Lund, et al, Pulsipher Family History Book (Privately Published, 1953), 22-23.

[32] Pulsipher, History, 23.

[33] Erastus Snow, cited in in John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge, MA and London, England: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012), 169-170.

[34] Turner, Brigham Young, 255-256.

[35] Turner, Brigham Young, 397.