One of the most pivotal events in the history of Mormon Pioneer Utah was the Utah War of 1857-1858. For the Mormons, the Utah Expedition brought an end to their semi-theocratic kingdom in the Great Basin. For the United States, this “war” drained the treasury and shaped the president’s reaction to impending southern succession on the eve of the Civil War. Zerah Pulsipher was a witness of many of the events of the Utah War as they unfolded and left a few recollections of what occurred. Like many accounts of the Utah War written by nineteenth-century Mormons, we see reverence for Brigham Young combined with the common experience of persecution and mob violence against Mormons shaping Zerah’s portrayal of the war. Historian Will Bagley has noted that the tradition that formed in Mormon portrayals of the war was that it was “part of an epic conflict between good religion and bad government, a story of persecution and vindication, and the triumphant tale of righteous warriors who marched with orders to ‘shed no blood.’”[1] This seems to apply to Zerah as well as any other Mormon.

Zerah was convinced that Mormonism was the true religion, and stated later in life that since his conversion in 1832: “I <had> been through nearly all the wars and Persecution that the People called Latter day saints have past through and have not yet found any thing to shake my faith.”[2] Included in this faith was the belief that Joseph Smith, Jr. was a prophet of God and the leader of the Church and Kingdom of God on earth. After the Prophet’s death in 1844, however, the matter of who was his legitimate successor was brought into question. The strongest option that presented itself was the Quorum of the Twelve, with Brigham Young at its head. Zerah, along with his family, chose to follow Young’s leadership, leaving Illinois with him in February 1846 and remained faithful disciples until their deaths several decades later.

Zerah yielded obedience to Brigham Young as the prophet-president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day for most of his later life. One early example of Zerah’s loyalty to Young came in a sermon preached shortly before they left Nauvoo, in which Zerah spoke of the Lord preserving the Quorum of the Twelve, and affirmed his support for following them, stating that: “Certain principles are enjoined on us at this time—to uphold the heads [the Quorum of the Twelve]—let there be a universal awareness that there is perfect safety and that they will live to a good old age and go down to their graves like shocks of corn fully ripe.”[3] Later—after Brigham Young had officially become President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints—Zerah recorded his conviction that Brigham Young “stood at the head on all power on Earth for the Church of Latter day saints,”[4] and consistently portrayed him as such.

As an early American convert to Mormonism, Zerah also shared many of the experiences that shaped the views the Latter-day Saints held about non-Mormons in the United States. The memories of persecution in Illinois and Missouri were burned deep into Zerah’s mentality, scarring him, causing a continuing fear of further mob violence, and leaving a distrust of non-Mormon intentions. As American historian Richard Lyman Bushman has noted: “For half a century, the war [in Missouri] poisoned Mormon memory.”[5] Over a decade after the events of the 1839 Mormon War, “Z. Pulsipher spoke on the pers[ecution] of L.D.S. in MO & exhorted there who [had] not passed thru the pers[ecution] to rejoice.”[6] In a sermon given January of 1851 in Salt Lake City, Zerah went as far as to state that Joseph Smith’s “blood was spilt & now those very men who shot him want to shoot us.”[7]

Image courtesy Wikipedia

One sees a further hardening of feelings towards the United States as a whole due to the lack of support the Mormons received in their troubles due to continuing mob violence in Illinois. After the violent death of Joseph and Hyrum Smith in 1844 Zerah’s son John recorded that, “The Whole nation is accessory to their death, because the murderers have boasted thro’ the States of their heroic deeds, and the first one of them has never been punished for committing that murder! And what is still more strange, is no man has ever been punished in the United States for killing a Mormon.”[8] Within two years, the remainder of the Saints fled Illinois. Seen through John Pulsipher’s eyes, the Saints were blameless while the United States as a whole was responsible for this injustice: “Just because we were Saints—our enemies were allowed to rob mob plunder and drive us from the pleasant homes that we have worked so hard to make, not satisfied with that, they would kill without cause and without fear, all seemed combined from the head of Government down.”[9]

These feelings were such that, when the United States came to recruit what has since been known as the Mormon Battalion—a move meant by the President Polk of the United States to “conciliate them [the Mormons], attach them to our country, & prevent them from taking part against us” by providing a means of dispensing hard cash to the Mormons—that the Pulsipher, like many other Mormon families, regarded the move as a plot against the Mormons.[10] Zerah commented that he thought the recruitment came “through the influence of Old Tom Benton who was a noted mobber in the first Missouri persecution and was then in the senate” and noted that it was a hardship for the Saints because “this left the church with old men children and many poor women while there husbans were fighting the battles of the united states.”[11]

The first prolonged contact with the U.S. Army in Utah—the Edward J. Steptoe expedition of 1854-1855—did not improve Zerah’s perception of the United States government and army. In a later autobiography, Zerah wrote: “About year =54 or =55 an Army came from the united states to the Valey commited some little depredations but were held at bay.” The depredations Zerah spoke of included incidents of public drunkenness and riot as well as fraternization with Mormon women. Most vexatious to the Mormons was the fact that upon departure the army was accompanied by as many as one hundred married and single Mormon women seeking an exit from the Church. This has been considered by historian William P. MacKinnon to be a “watershed in what by the end of 1855 had become an accelerating, potentially violent deterioration in Mormon-federal relations.” By the time Colonel Steptoe’s detachment left the Salt Lake Valley for California in May 1855, Brigham Young had vowed to never again allow federal troops into Utah and in proximity to its women.[12] Pulsipher recalled this feeling in his own way by recollecting a friendly conversation with an officer at Camp Floyd after the arrival of the Utah Expedition in 1858. In this conversation, the officer asked: “What did your people think they could do with 3000 men armed as they were[?]” Zerah’s response was that: “Our people patience had been so perfectly worn threadbare in consequence of the various depridations that had been committed by the other soldiers and strangers upon both male and female that they were hard to hold.”[13]

On the Utah War

Zerah’s recollections of the Utah War are better understood when the foregoing discussion of his belief in the divinity of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and obedience to its leader, Brigham Young, combined with the experiences that created something of a persecution complex in Zerah are kept in mind. Throughout his autobiographies, Zerah portrays the events of the Utah War as a vindication of his religion and people against a corrupt, Gentile nation. Pulsipher’s coreligionists are generally portrayed as doing no wrong while the actions of the United States are portrayed as a series of blunders that worked to ultimately help the Mormons. In Zerah’s eyes, the initial cause of the conflict was that: “Br[other] Brigham gave some strong prophetic language relative to <the> united states of America,” following which “the President and Congress became very hostile to us and <seemed> to have a design <to> form us like themselves or destroy us[.] Therefore they sent an army to bring us too or destroy us.” To make his feelings clear that the expedition turned out to be a blunder, he noted that in time: “The President and Congress saw their mistak in sending the army here notwithstanding they had charged us with treason and many other offenses. They sent commissioners here forgave all our sins against them and wished peace and tranquility.”[14]

It must be noted that in reality, while accounts of atrocities and horrors in Utah that inspired the Utah Expedition were greatly exaggerated in the States at the time, the Mormons were not completely guiltless. Poor interactions with Federal officials; mob action in Salt Lake City that resulted in the destruction of property belonging to Federal Judge George P. Stiles; the bombastic and sometimes violent rhetoric of the Mormon Reformation of 1856-1857; and the murders of William, Beeson, and Orrin Parrish along with George Potter in 1857 were causes of considerable concern to the U.S. government.[15] Still, in retrospect, those events were probably not sufficient cause to pit nearly one-third of the U.S. Army against the country’s largest, most experienced militia on the eve of the Civil War, resulting in the near-depletion of the U.S. Treasury; the forced resignation of a secretary of war; the bankruptcy of the nation’s largest freighting company; and severe damage to the reputation of the president of the United States and his nerve for confronting southern secession.[16] Yet, the blameless appearance of the Mormons in Zerah’s writings says much about his about his feelings towards his own people and religion.

When it comes to relating what Bagley referred to as a “triumphant tale of righteous warriors who marched with orders to ‘shed no blood,’” Zerah portrayed the Mormons as having the upper-hand throughout the conflict with the U.S. Army at their mercy. In relating the experience of the Mormon militia raiding the army companies and ensuring that they stayed the winter in Wyoming, he merely said that: “We found that it was not wisdom to let them [the Utah Expedition] come in that way” because they “had some appearance of hostility” and “we did not like their hostile spirit nor their habits.” So, he continued, “we were not willing to trust them to come in to our midst with those felings [and] we held them in the Mountains till we were ready to receive them.”[17] During the conversation with the army officer in Camp Floyd, he told the officer that:

It is my opinion that if the men of salt <lake> city were to fall upon you that they would dstroy you at a Breakfast spell and salt lake is but one city to a great many both north and south and west[.] I recollect at one time while in our Sunday meting while you were in the Mountains in the winter that <some> of the authorities wanted to let our men fall upon you but Brigham held them back and took that influence away saying that there were many in that army that were honest men and if we should destroy <them> we should do wrong therefore they were held back for further consideration and if they pleas they may thank Brigham Young for that.[18]

It is interesting to compare this confident assertion—written down after the War had concluded—with the journal entries of his eldest son, John Pulsipher, during the course of the war. At first, fear mixed with defiance shines through:

The news from this day [July 26, 1857] is that Hell is boiling over and the devil is mad. The US mail is stopped and an army is coming to kill us. Parley Pratt is murdered. . . .

August 16 . . . This looks like former times when we have had to leave our homes and hard earned possessions—but we are very willing to prepare for safety, for we have no confidence in the government officials.[19]

As events proceeded that fall, the Pulsiphers became a bit more confident: in late October, 1857, John “received a letter from brother Charles of the 17th. Says the U. S. Army, as they call themselves, are determined to come in—and say they are fully able to do so—yet he says we are whipping them without killing a man having taken their stock, burned their freight trains and now have burned Fort Supply and Bridger to save them from falling into their hands.”[20] When the army began to advance again the next March, however, John was not as confident about the situation: “The U.S. Army east of us have wintered very well and are threatening to come upon us and make a final end of all that will not join them. Truly this is a trying time, Destruction stares us in the face which ever way we turn.”[21] After an April 6 meeting with Brigham Young, though, John recorded that he “felt firstrate and perfectly satisfied as to the triumph of Israel.”[22] On his journal entries go, cycling through being fearful, defiant, and triumphant as events unfold. It seems that with the problem settled, Zerah was able to remember the triumphs more than the fear.

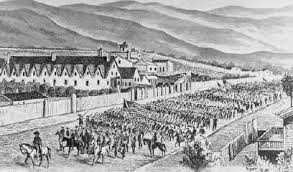

As the army arrived, Zerah—as a ranking official in the Church and as a city council member—remained in Salt Lake City to watch the army’s entrance into the city while the “women and children were moved to the south.” He owned property not far from the location of Camp Floyd, where the army settled after their arrival in the Territory. This was both a blessing and a curse for the Pulsiphers. It was a blessing because Zerah was able to meet a few officers in the army and found that “the[y] <were> disposed to be friendly” and that they “treated me very kindly.”[23] What is more, the Army provided economic opportunities and the chance to obtain badly-needed supplies. As Zerah recalled, after the army settled down and the Mormons were offered amnesty by the Federal government: “We all moved back to our possessions peacefully[.] In the mean time we were rather destitute of clothing but speculators followed the army and brought more goods to the Valey than was ever brought before so that this people were decently clothed[.] All this we considered direct from the hand of god to supply our wants.”[24] The capstone of this beneficial trading came when the camp was evacuated at the start of the U.S. Civil War in 1861. There followed what historian Leonard J. Arrington characterized as “probably the largest government surplus property sale yet held in the history of the nation.” Millions of dollars of property were sold for a fraction of their value.[25] Zerah recollections of this event were that: “After a short time they began to dwindle away Till they all left and left many thousand dollars worth of property which they <sold> for <a> trifling sums.”[26]

The army’s presence was also a curse in Zerah’s eyes because of poor behavior on the part of some of the soldiers and the moral influence they had on the people of Utah. He recalled problems with a Camp Floyd herdsman driving cattle onto the Pulsipher farm, causing some damage to his property, and noted “that a few [residents from Camp Floyd] would come into town some times and commit depredations for which <we> would chasten them.”[27] Historians James B. Allen Glen M. Leonard also observed that “the blessing was mixed . . . for all the vices of civilization also were introduced and nurtured by the army and its satellite community.”[28] On a similar note, Zerah commented—quite pointedly—that:

Evils have followed the army[—]such a herd of abominable <characters> have come in the wake that lying, horeing [whoring,] gambling, robing, stealing, murdering till it seemed as thoug they were determined to break up all law and order in the territory[.] They brought with them much spurious liquor which still furthered them in their abominations and <many> of our people who were weak joined with them in their wickedness especially the rising generation who imbibed their habits this gave us some trouble to labour and keep the church in order.[29]

Conclusion

This last statement seems to capture the motivations and drives that shaped Zerah’s portrayal of the Utah War quite well. Concern for preservation of private property, morality, and order in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints with Brigham Young at its head caused Zerah to portray the Utah War as a tale of conflict between righteous faith and corrupt government. His belief in the leadership of his prophet-president Brigham Young and repeated experiences of mob violence colored his perceptions of the war as the persecution and vindication of a Godly but hated people. In this regard, Zerah Pulsipher’s recollections of the conflict match many other Mormon reminiscences of their glorious defeat of “Johnston’s Army.” Whether right or wrong, these portrayals reflect on both shared experiences of the Utah Mormons and their obedience to President Brigham Young.

For a slightly different version of this essay, which took first place in the 20th annual Arrington Writing Award competition held at Utah State University click here.

Sources

[1] Will Bagley, introduction to At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858 by William P. MacKinnon (Norman, OK: The Arthur Clark Company, 2008), 13.

[2] Zerah Pulsipher, “Autobiographical Sketch,” undated, MS 753.3, Church History Library (Church Archives), Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, 4.

[3] Minutes of 11 January 1846, Meeting of Seventies, notes by Thomas Bullock, in Historian’s Office general church minutes 1839-1877, CR 100 318_1_48_5, Church History Library (Church Archives), Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[4] Zera Pulsipher record book, circa 1858-1878 MS 753 1, Church History Library (Church Archives), Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah, 2.

[5] Richard Lyman Bushman, Joseph Smith: Rough Stone Rolling, with the assistance of Jed Woodworth (New York: Vintage Books, 2005), 372.

[6] Minutes of 1 September 1850, Meeting in Bowery, Salt Lake City, in Historian’s Office general church minutes 1839-1877, CR 100 318_2_36_8, Church History Library (Church Archives), Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[7] Thomas Bullock, booklet (#10), 12 January 1851, in Historian’s Office general church minutes;1846-1850, CR 100 318, Church History Library (Church Archives), Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah.

[8] John Pulsipher, Journal, 28.

[9] John Pulsipher, Journal, 29-30, emphasis added.

[10] John G. Turner, Brigham Young: Pioneer Prophet (Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2012), 150.

[11] Zera Pulsipher record book, 24.

[12] William P. MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, Part 1: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858 (Norman, OK: The Arthur Clark Company, 2008), 48-50.

[13] Zera Pulsipher Record book, 57.

[14] Zerah Pulsipher Record Book, 26-27.

[15] See Thomas G. Alexander Utah: the Right Place, revised edition (Salt Lake City: Gibbs-Smith Publisher, 1996) , 125.

[16] MacKinnon, At Sword’s Point, 17.

[17] Zera Pulsipher Record Book, 27, 56.

[18] Zera Pulsipher Record Book, 57-58.

[19] John Pulsipher, A Mormon Diary as told by John Pulsipher, ed. Donald Neil Burgess (Idyllwild, CA: M3RDPOWER Press, 2006), 100-101.

[20] John Pulsipher, A Mormon Diary, 105.

[21] John Pulsipher, A Mormon Diary, 109.

[22] John Pulsipher, A Mormon Diary, 110.

[23] Zera Pulsipher Record Book, 56-57.

[24] Zerah Pulsipher, Record book, 26

[25] Leonard J. Arrington, Great Basin Kingdom: An Economic History of the Latter-day Saints 1830-1900 (Lincoln, NE: University of Nebraska Press, 1966), 197-199.

[26] Zera Pulsipher Record Book, 56-57.

[27] Zera Pulsipher Record Book, 58.

[28] James B. Allen and Glen M. Leonard, The Story of the Latter-day Saints, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 318.

[29] Zera Pulsipher Record book, 26-27.